Summary

In

response to a formal request, the CRN has filed a formal critique of

California's Drug Medi-Cal (DM-C) program with the Legislative Analyst's

office in Sacramento. The critique concludes that DM-C has created a

system of care in California that is far below any standards of "Best

Practice" in the substance treatment field. Standards of care are

so low, the report suggests, that California is in violation of federal

Medicaid laws requiring that services be sufficient in amount, duration,

and scope to reasonably achieve their purpose

The report concludes

that "to conform to science-based principles and best practices,

DM-C coverage must be expanded for both adults and adolescents to include

reimbursement for residential services; day treatment; detoxification

(including standard detoxification medications); program-based case

management; clinically justified individual counseling; acupuncture

for acute and post-acute withdrawal, and services that are delivered

in community-based settings. Coverage for collateral services for family

members and 'significant others' must also be expanded to include individual

counseling, group counseling, and therapy."

Defining

the interest of the recovery community

The mission

of the Community Recovery Network (CRN) is to provide ongoing leadership

in community responses to alcohol and other drug (AOD) problems in California.

Drug Medi-Cal (DM-C) policies significantly impact community responses

to AOD problems. DM-C is important because many of those eligible for

the program - such as the severely mentally ill, persons with AIDS,

and recipients of public assistance, including minors - are disproportionately

impacted by substance disorders; additionally, DM-C Standards are often

used by Counties to define and govern non-DM-C treatment services to

avoid disparities in treatment and possible discrimination litigation.

Fiscal

imperatives for improving DM-C

Members of

our constituencies have expressed dismay at the enormous cost to the

citizens of California when AOD problems are not competently addressed.

The cost of these problems in the United States is estimated at $276

billion per year (NIDA/NIAAA,

1997). California's share of this cost, based on population, is

$35 billion. One could presume that a majority of that cost is imposed

by persons whose alcoholism or drug addiction is the most chronic and

severe, of which a disproportionate number are likely to be Medi-Cal

recipients.

Based on

prevalence estimates of 7.3% suggested by the most recent AOD survey

data (SAMHSA,

2002), we can estimate that the number of Californians in need of

treatment for chemical dependency is just under 2.5 million. In spite

of an often cited study by the State of California (DADP,

1994) showing that savings to taxpayers outpaced the public cost

of treating addicts by a 7-1 margin, California spends less than $600

million on treatment (CASA,

2001), adequate to treat just over 6% of those in need.

In a study

of the impact of untreated AOD problems on State governments conducted

by the Center for Substance Abuse at Columbia University (CASA,

2001), the percentage of California's State budget that is related

to AOD problems was estimated at 15.2%. Of that, only .4% was spent

on treatment, and the rest was spent on "shoveling up the wreckage"

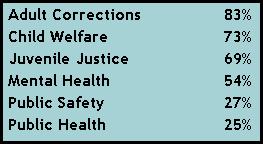

of untreated AOD problems. Portions of California departmental costs

related to AOD problems are estimated in the CASA study as follows:

Applying

only these percentages to California's 2002-03 budget, the cost to the

State of not adequately addressing alcohol and other drug problems is

$14.3 billion - over 14% of the total budget.

CRN's constituency

believes strongly that we cannot afford this luxury given California's

current fiscal shortfalls and deficits.

The

absence of effective management in the DM-C system

The Sobky

v. Smoley lawsuit in 1994 ended limits on utilization of DM-C by ruling

that drug treatment is an entitlement under Medicaid guidelines. In

response, utilization of outpatient and day treatment services increased

dramatically. There were no caps on rates, and reimbursement occurred

for clinic "visits" only, not for specific services. While

providers were required to have perfunctory "Utilization Review

Committees," ultimate decisions concerning both utilization of

services and the rates charged for those services were being made by

the service providers themselves without external regulations.

Interestingly,

an analogous problem was occurring in the private sector; hospital-based

chemical dependency treatment programs were charging private insurance

companies thirty to forty thousand dollars and more for thirty-day residential

programs, often with no limitations on the number of patient repeat

visits.

In short,

the chemical dependency service delivery system - both public and private

- had become a fiscal "runaway train."

While the

response in the private insurance sector was either strict managed care

practices or the elimination of chemical dependency benefits altogether,

the response of the DM-C system in 1996 was cost containment achieved

by constricted services such as limits imposed on rates and on the number

and kinds of services a client could access. The DM-C system appeared

- because of Sobky v. Smoley - unable to adopt the kinds of managed

care strategies that characterized other venues. The services received

by clients under DM-C, therefore, came not to be based on clinical guidelines

or recovery principles but rather on constrictions devised to contain

costs. These constrictions remain in place today.

Not only

are such constrictions without reference to our knowledge about successful

recovery, or to research-based clinical principles or science-based

treatment practices, but they sometimes frustrate the goals of other

State-sponsored services and result in far greater costs than those

that were "saved." For example, a chemically dependent pregnant

woman on the caseload of Child Protective Services will be eligible

for DM-C services during her pregnancy, but her eligibility will be

removed shortly after her child is born. With non-DM-C perinatal day

treatment services experiencing dramatic waiting lists in many Counties,

this can result in substance relapse, loss of custody of the child,

and the ultimate failure of family reunification. Or a chemically dependent

severely mentally ill person who is in need of comprehensive residential

treatment will find that it is not a covered Medi-Cal benefit and hence

unavailable in the County, resulting in psychiatric emergency. In these

cases, the "cost containment" measures result in costs to

the State that are far greater than those of treatment, such as out-of-home

foster care placement and exorbitant psychiatric emergency services.

Not surprisingly,

these "cost containment" measures in 1996 were soon followed

by the elimination of State mandates for providers to perform the monthly

utilization review that had provided the only mechanism of outside monitoring

of quality assurance in the system. Although an annual Utilization Review

mechanism was to have been instituted by the State, this has occurred

only sporadically, and the only specific control on provider utilization

of DM-C is the occasional and expensive provider audit.

"Moderate

Treatment" and Best Practices

Prior to

Sobky v. Smoley, the DM-C system was presented in theory as a program

for treating only "moderately impaired" chemically dependent

persons. Those severely impaired were to be referred elsewhere, presumably

to residential treatment facilities in those Counties where such services

were available. The system still carries that presumption. The problem

is that Sobky v. Smoley cannot be interpreted to apply solely to chemically

addicted individuals who are "moderate users." Indeed, all

persons who are diagnosed with chemical dependency and who are Medi-Cal

eligible are entitled to treatment that meets reasonable "best

practices" standards. DM-C, however, does not reimburse for services

and interventions of a variety and at a frequency that would conform

to the principles governing best practices and science-based treatment

of substance disorders such as those defined by the National Institute

on Drug Abuse's "Principles

of Drug Addiction Treatment" (NIDA, 1999) and by the Center

for Substance Abuse Treatment's "TIPS,"

(CSAT, 2002). California's DM-C program indeed appears to be in violation

of 42

USC 1396a(a)(10)(B), which states that "… service(s) must

be sufficient in amount, duration, and scope to reasonably achieve (their)

purpose (and) the Medicaid agency may not arbitrarily deny or reduce

the amount, duration, or scope of a required service ... to an otherwise

eligible recipient solely because of the diagnosis, type of illness

or condition."

To conform

to science-based principles and best practices, DM-C coverage must be

expanded for both adults and adolescents to include reimbursement for

residential services; day treatment; detoxification (including standard

detoxification medications); program-based case management; clinically

justified individual counseling; acupuncture for acute and post-acute

withdrawal, and services that are delivered in community-based (sic.

non-clinical) settings. Coverage for collateral services for family

members and "significant others" must also be expanded to

include clinically justified individual counseling, group counseling,

and therapy.

Legislation

has been introduced in the past to adapt DM-C to the "rehab model"

utilized by the Mental Health system, adding many of the benefits described

above. While few would argue that it is acceptable for the regulations

governing public treatment for chemical dependency in California to

be below standards of best practice, it will be difficult for the DM-C

program to achieve best practices standards unless it also incorporates

realistic monitoring and management mechanisms that prevent abuse of

the system. Unlike Short-Doyle Medi-Cal reimbursement for mental health

services, AOD services for Medi-Cal recipients are still defined as

an entitlement under federal Medicaid guidelines by Sobky v. Smoley.

Extending reimbursed services to include case management, residential,

and other services, is therefore not politically feasible unless there

are intelligent mechanisms in place to manage the costs and utilization

of this entitlement. These mechanisms are allowed under 42 USC 1396a(a)(10)(B),

as follows: "The agency may place appropriate limits on a service

based on such criteria as medical necessity or on utilization control

procedures." In order to achieve this, the State Alcohol and Drug

Program will need to obtain a Federal Medicaid Managed Care waiver from

the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The CRN also

urgently proposes an extension of the DM-C benefit for women under the

jurisdiction of Child Protective Services who have lost custody of their

children for reasons relating to their chemical dependency when family

reunification is the ultimate goal. Restrictions could be placed on

this extension, such as a requirement to comply with the chemical dependency

treatment plan.

Distinguishing

Characteristics of Substance Disorders

There is

another systemic problem with the DM-C program. Medi-Cal in general

has evolved to provide reimbursement mechanisms for the treatment of

physical illnesses. While alcoholism and drug addiction have been identified

by the medical and research communities as diseases, three very significant

factors distinguish substance disorders from other diseases. These three

factors must be systemically addressed in order to optimize successful

outcomes in any system of care.

- Persons

with other illnesses generally seek medical care when their condition

becomes symptomatic. This is not true of persons with substance disorders

due to the stigma, denial, hopelessness, impaired judgment, and other

issues associated with AOD problems.

- While

certain other medical interventions require a period of rehabilitation

that involves non-medical services, and while certain other chronic

diseases require behaviors or actions on the part of the patient in

order for the disease to remain in remission, long term recovery from

substance disorders uniquely depends in most cases upon ongoing, patient-initiated

activities and involvement with non-professional community resources

(e.g. peer-support groups).

- Persons

with substance disorders - particularly in cases where the condition

has progressed to the degree that public sector services are required

- typically have concomitant public health, mental health, and social

issues whose resolution is tantamount to substance recovery and which

must therefore be thoughtfully incorporated into the AOD treatment

continuum.

These three

distinctions suggest a critical need for comprehensive case management

services (currently not a covered benefit under DM-C). But the recovery

community's collective experience with successful recovery, as well

as the need for quality assurance and cost effectiveness within the

DM-C system, suggests that traditional case management as utilized in

the health and mental health systems of care may not adequately or appropriately

address all of these unique characteristics of substance disorders.

The

Solution

Based on

the problems we have described so far, it may be concluded that the

solution to improving the DM-C program must, at a minimum, include the

following:

- Services

must be reimbursed that conform to research-based treatment principles

and best practices. While Sobky v. Smoley prohibits the State from

discriminating about who becomes DM-C certified, it does have the

authority to establish the clinical standards under which all providers

must operate their treatment services. Guidelines should include,

at a minimum, those defined by the National Institute on Drug Abuse's

"Principles

of Drug Addiction Treatment" (NIDA, 1999) and by the Center

for Substance Abuse Treatment's "TIPS,"

(CSAT, 2002), including especially, for adolescent treatment services,

TIP 31: "Screening and Assessing Adolescents For Substance Use

Disorders," and TIP 32: "Treatment of Adolescents With Substance

Use Disorders," and the formal adolescent

treatment guidelines developed by California's Department of Alcohol

and Drug Programs (2002)

- The DM-C

system must have intelligent mechanisms governing the authorization

and utilization of services. Such management requires fundamentally

that the decisions made about what services are appropriate to an

individual client at what stage in his or her recovery and at what

frequency need to be made by an entity other than the one that will

provide the service and receive the reimbursement. These decisions

also need to be made by an entity that is neutral to local political

agency or "turf" issues to assure that utilization decisions

are based to every extent possible upon what services will most likely

result in the client's successful recovery.

- Mechanisms

need to be built into the system of care to enhance long term recovery

as opposed to simply encouraging people to enter treatment. Some administrators

believe that the greatest current cost burden on the treatment system

is not the individual who is a success and who therefore heavily utilizes

services for a long period of time, but rather the failures - those

individuals who access the system again and again but who never achieve

recovery.

While our

critique has made specific references to the problems of the DM-C program,

it is difficult to develop realistic and comprehensive solutions to

these problems without considering the overall response to AOD problems

at the County level. As has been noted, DM-C guidelines are used in

many Counties to set standards of care for non-DM-C treatment services.

Conversely, in other Counties, DM-C has resulted in a "2-tier"

system where Medi-Cal eligibility influences a person's qualification

for certain services. Less restrictive Net Negotiated Amount (NNA) funding

is able to fund a scope, duration and intensity of service which is

more appropriate clinically. It is not possible for clients of programs

funded solely by DMC to receive the same level of treatment that a client

can get in a program funded by NNA or NNA + DM-C.

It is the

strong belief of the CRN that the quality, consistency, appropriateness,

and timeliness of services received by residents of any County should

not be dictated by any status. When someone residing in a County has

an alcohol or other drug problem, the case can be made - financially,

ethically, and morally - that it is in the vital interest of that County

(and hence of the State) to respond to that problem with dispatch, and

to dedicate any and all resources necessary until successful recovery

for that individual is achieved. Failure to do so inevitably results

in enormous emotional costs to the person themselves and to their family,

friends, and loved ones, as well as lost productivity and colossal costs

to taxpayers for criminal justice, public health, and social services.

So, while

it may be beyond the scope of the Legislative Analyst's current investigation,

the CRN believes that any recommendations to the legislature concerning

DM-C should be ultimately viewed in the context of the entire AOD system

of care. The last effort by the State to address comprehensive system

of care issues deteriorated into a recommendation for modifications

in data collection (LAO,

1999).

An

Independent, Entry Level, Recovery Advocacy System in Each County

CRN proposes

the creation in each County (and in representative regions for Counties

with populations under 30,000) of a "Recovery-Based Case Management

System." The system would be operated under contract with the State

or County by a private entity who was not a DM-C or treatment service

provider, and who would perform the following functions:

- A 24-Hour

per day drug hotline and response team. Any private citizen residing

in the jurisdiction, or any professional such as a physician or therapist,

or any public employee such as a probation or parole officer, public

health or social service worker, could access the response team with

a single phone number. The team from which the person responding would

be selected would represent the diversity of the jurisdiction to assure

cultural and linguistic competence in the response. Requirements for

all response team members, who would work under clinical supervision,

would include (a) an Alcohol and Drug Counseling Certificate or its

equivalent; (b) competence in addiction severity assessment, family

interventions, brief crisis counseling, and motivational interviewing,

and (c) comprehensive knowledge of all community service providers,

including knowledge of all means by which people achieve and maintain

recovery from AOD problems, and of the community resources relative

for each.

- Comprehensive

and mobile case management services. The assigned Response Team member

would assess the individual referred to the system and the environment

in which they are functioning and work to remove any barrier to successful

recovery for both the individual and the family members. The person

would also authorize services within the formal treatment provider

network of the County for both the individual and his or her family

members, and would assist the client in accessing ancillary (non-treatment)

services that are deemed important to support the persons long term

recovery (such as mental health, public health, and vocational and

other services, and safe housing). These persons would operate in

conjunction with law enforcement, Mental Health crisis teams, social

workers, and others who encounter people with AOD problems in the

community

Recovery

Advocacy in the AOD treatment system is not an unprecedented concept.

Many drug court venues in California and around the country have adopted

a "Court Liaison" function - a person who mediates between

the court, probation, and treatment system on behalf of the client or

offender. The role of the Liaison is to assess and explain options to

the client, to propose referral recommendations to the drug court judge,

and then to "leave no stone unturned" in assuring that the

client is successfully engaged and retained in the recommended services.

Many Counties in California adopted a similar "recovery advocacy"

model for their perinatal case management services, and similar case

management services were successfully provided to SSI recipients before

the elimination of the alcoholism and drug addiction disability benefit.

The recovery

community has learned that not everyone with AOD problems needs formal

treatment. For many people, 12-Step and faith-based activities and their

equivalent, which may or may not be in combination with clean and sober

housing, are adequate for successful recovery. The proposed system would

be distinguished from traditional case management services that are

used in the public and private health sector in that their primary objective

would not be exclusively clinical (e.g. to access clinical services),

but to assist the client in engaging in those natural community supports

that enable long term recovery.

Based upon

the 2.5 million Californians who are estimated to be severely impacted

by alcohol and other drug problems, the cost of such a Recovery-Based

Case Management system, with an average case load of 70 persons, could

be estimated at $1.5 billion. However, this system should not be construed

as supplanting the significant need for additional treatment resources.

Indeed, the system's effectiveness would be severely compromised if

implemented in the current environment of resource-scarcity and substandard

services.

What

would a Comprehensive Treatment System Cost?

If California

were to invest in a comprehensive infrastructure to provide in each

County a realistic and effective response to alcohol and other drug

problems, the cost would depend significantly upon whether or not the

State is able to enact effective "Substance Abuse Parity"

legislation. This is because an estimated 75% of persons needing treatment

or recovery support services are in the work force (SAMHSA, 1999), and

many of these individuals are privately insured. A relatively weak parity

bill (SB599) was passed last year, but was withdrawn under threat of

veto by the Governor.

Using an

average treatment cost of $5,000, what might a comprehensive treatment

and recovery infrastructure for California require in terms of a public

investment? Of the 2.5 million needing recovery, we would estimate that

70% would either (a) require recovery support only (with no formal treatment),

or (b) be able to self-pay for treatment, or (c) be privately insured.

This portion of the 2.5 million people would therefore require no public

investment unless the State is unable to enact private insurance parity

legislation. Then the investment required for this group is estimated

at $3.5 billion.

We would

estimate the remaining 30% of the population as follows:

| |

Percentage |

Number |

Investrment |

| Uninsured

and requiring public treatment |

12% |

300,000 |

$1,500,000,000

|

| Eligible

for Medi-Cal (includes Federal match |

18% |

450,000 |

$2,000,000,000

|

| Recovery-Based

Case Management System |

|

|

$1,500,000,000

|

| Current

Investment |

|

|

($600,000,000) |

| Total

Infrastructure Investment: |

|

|

|

|

With Private Insurance Parity |

|

|

$4,400,000,000

|

| Without

Private Insurance Parity |

|

|

$7,900,000,000

|

Two things

are important to note when considering this investment:

- Unlike

the $35 billion that Californians are currently spending each year

on untreated AOD problems, this investment is not a continuing annual

cost. As people with severe alcohol and other drug problems begin

to successfully recover as the result of this investment, the cost

of maintaining the infrastructure declines dramatically.

- This estimated

cost (like California's

proposed $9.9 billion high speed train) should be viewed not as

an added cost but as a long-term investment. Currently, any

fiscal impact of the AOD treatment investment dollars cannot be measured

because the investment is so small. For example, the $120 million

invested in treatment as a result of the Substance Abuse and Crime

Prevention of 2000 (Proposition 36) - even under the sub-standard

treatment provided by the current system - is adequate to treat less

than 11% of the chemically dependent persons who are involved with

the criminal justice system, and less than 2.5% of the total population

who are in need of treatment or recovery support services. Therefore,

even success rates that are far above average will have a negligible

impact on the overall cost of criminal justice services in the State.

The comprehensive infrastructure suggested, however, even with lower

than average success rate, would reduce the current $14.3 billion

cost to the State to just over $4 billion in ten years.

CRN's

Recommendations

In summary,

the CRN recommends:

- That application

be made for a Managed Care waiver from the Center for Medicare &

Medicaid Services.

- That the

State Plan be amended to implement the "Rehab option" for

AOD services.

- That the

California Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs assemble stakeholders

including County Alcohol and Drug Program Administrators, representatives

of the recovery community, and providers, to address strategic issues

concerning the design of the Recovery-Based Case Management System.

Sources

Cited

CSAT, 2002,

Treatment Improvement Exchange, Treatment

Improvement Protocols (Best practice guidelines for the treatment

of substance abuse).

Department

of Alcohol and Drug Programs (1994), State of California, "Evaluating

Recovery services: The California Drug and Alcohol Treatment Assessment."

1700 K Street, Sacramento, CA 95814.

Department

of Alcohol and Drug Programs (2002), State of California, "Youth

Treatment Guidelines." 1700 K Street, Sacramento, CA 95814.

Legislative

Analyst's Office (July 13, 1999), "Services

Are Cost-Effective to Society Substance Abuse Treatment in California,"

LAO Publications, 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

CASA (January,

2001). "Shoveling

Up: The Impact of Substance Abuse on State Budgets." National

Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University.

National

Institute on Drug Abuse/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

(1998), The

Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse in the United States, U.S.

Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1998.

NIDA, 1999.

Principles of

Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. National Institutes

of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

SAMHSA, 1998

(1998 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse), U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services. Rockville, MD.

SAMHSA, 2002

(2001 National

Household Survey on Drug Abuse), U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services. Rockville, MD.

|

|